Sustainable Development Goals > People

ADLAM - AN ALPHABET TO PRESERVE A CULTURE

McCANN, New York / MICROSOFT / 2023

Awards:

Overview

Credits

Overview

Background

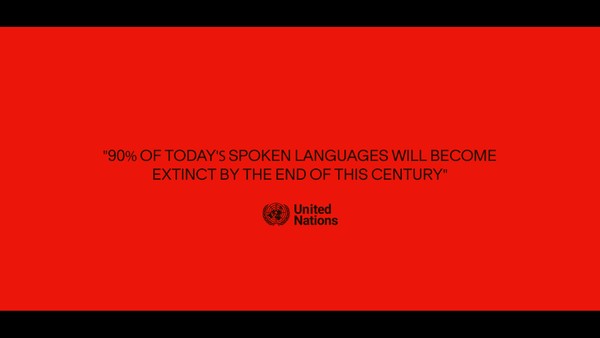

The United Nations estimates that "90% of today's spoken languages will become extinct by the end of this century". Pulaar, the native tongue of the Fulani people of West Africa, was one of them…until recently.

Without an alphabet of their own, 40 million Pulaar-speaking Fulani were forced to use the alphabets of other cultures to write their history, songs, and stories—causing rampant illiteracy and cultural erosion.

This is a story of how inventive typography design, creative thinking and technological problem solving helped optimize and promote a new alphabet for an ancient people. This is a story about how creativity can help curb the blight of illiteracy, help return a fading culture to its rich heritage, and promote a more sustainable future for all.

Describe the cultural / social / political climate and the significance of the work within this context

For centuries, the Fulani people have transferred traditions, knowledge and information through the spoken word of Pulaar, relying on a mixture of French and Arabic when the need for written records arose. This created a massive illiteracy problem in the community, since Pulaar speakers struggled to reconcile the sounds and nuances of their language with letterforms that were foreign to them and didn’t properly translate their words or intentions.

When ADLaM was created by the Barry brothers, it gave the Fulani an alphabet born of their unique needs and culture.

But as the diaspora expanded and the Fulani increasingly remained connected through modern technologies like social media, the alphabet needed to be updated and adapted to meet the demands of a digital world — ensuring ADLaM, and the culture it represents, live on for future, digital-first generations.

Describe the creative idea

To help preserve the Pulaar language — and help fight illiteracy within the community — we worked with the Barry brothers to rebuild ADLaM for the digital age and put it in the hands of the 40 million Fulani across the globe connecting through technology.

While alphabets usually take hundreds of years to evolve into their final form, we were able to speed the process, using real-time community feedback to revise ADLaM’s outdated letterforms.

This new version of the alphabet is being made accessible on over one billion devices around the world, enhancing the Fulani’s access to educational, business and social tools—ensuring both the language and culture ADLaM represents live on for generations.

And because schools are the primary entry point for learning the alphabet, we developed a collection of learning materials — books and posters in print and digital — that celebrate the rich culture of the Fulani.

Describe the strategy

For generations, the 40-million-person Fulani diaspora relied on the spoken word of Pulaar — their native tongue — to pass down traditions and history, and to conduct business. But as their culture transferred to the digital world, their language needed to as well.

We aimed to help the Fulani people — particularly women and children, who suffered from especially high illiteracy rates — with the preservation of their culture by creating a new and optimized version of their alphabet that would help them stay connected to their global community and navigate an increasingly digital world on their own terms.

We not only made ADLaM letterforms easier to read and write, but also helped to make ADLaM easily adoptable by schools building new curricula around the alphabet. Additional learning resources helped prepare women and students to join the digital world, feeling more included as the community advanced into the 21st Century.

Describe the execution

After ADLaM was encoded, community feedback revealed major revisions were needed to make the alphabet easier to learn, read and write. Working with the Barry brothers, typeface experts and Fulani graphic culture specialists, we revised the letterforms of the alphabet creating a new, optimized version.

Taking inspiration from Fulani visual culture, we researched hundreds of traditional textile patterns and designs, uncovering their unique meanings to define the final form of the characters. By weaving their heritage into the solution, the Fulani saw themselves in their very own alphabet.

The revised alphabet is being made accessible on over 1 billion devices running Microsoft 365 Office, through a new typeface — ADLaM Display.

We then developed learning tools to promote literacy in Guinean schools, including a children’s book, instructional workbooks and classroom posters designed to teach the alphabet.

Describe the results / impact

These combined efforts helped ADLaM gain popularity within the Fulani community — helping secure the future of the alphabet and their culture for future generations:

1. ADLaM is being made accessible on over 1 billion devices worldwide.

2. The alphabet will also be used to preserve the Bambara, Bozo and Dogon languages due to shared phonology and syntax with Pulaar.

3. Guinea’s Minister of Education is taking steps to ensure ADLaM is recognized as Pulaar’s official alphabet.

4. The first two ADLaM-focused schools will open this year in Guinea and for the first time, allow Fulani children to study a full curriculum in their native tongue.

5. The Government of Mali is in the process of recognizing ADLaM as an official alphabet in their constitution.

6. The new alphabet is being used on social media to fight illiteracy.The project also sparked the co-creation of the first ADLaM dictionary, through #ADLaMRe.

More Entries from Quality Education in Sustainable Development Goals

24 items

More Entries from McCANN

24 items