Radio and Audio > Innovation in Radio & Audio

AUDITORIAL

R/GA, London / GOOGLE / 2022

Awards:

Overview

Credits

Overview

Write a short summary of what happens in the radio or audio work.

This customisable storytelling experience is designed to make online news and storytelling, accessible and enjoyable for blind and low vision audiences.

The Auditorial storytelling website presents - ‘The Silent Spring’ ; story of Bernie Krause, and his 50 year career spent recording the sounds of the natural world, produced by the Guardian, which can be adapted using 22 audio and visual controls — enabling the user to experience the same story over 100 different ways.

This project is intended to spark a broader discussion about how the web at large might be designed more flexibly, to become a more inclusive place for people with disabilities.

Translation. Provide a full English translation of any audio.

The Silent Spring

By The Guardian

Part 1 - “These weren’t normal fires.”

“I don't mind the fires so much. Because the fires, if they're normal fires are rejuvenating in many ways, and we need them. But these weren't normal fires. These were the most extraordinary things I've ever experienced.”

While the world watched the 2017 northern California wildfires, Bernie and Kat Krause lived them.

Kat still remembers waking up in the middle of the night and fleeing for her life.

“A tsunami of fire descended upon us and all you have time to do is flee. You don't think. It transcends logic about even what's happening. You just go like a deer in the forest.

“It's as close as I think I've ever gotten to that purely atavistic, sort of animal sense of survival.”

— Kat Krause

The fires became a tangible example of the climate breakdown. Global heating likely caused the large area of dried plants that were susceptible to fire. A delayed rain season dried the plants even more. When the fires started in October that year they quickly grew into the most destructive in California’s history.

Among the more than US$10bn worth of damage was Bernie and Kat’s home, roughly 15 miles from Santa Rosa, California. It was a rural home surrounded by nature. They called it Wild Sanctuary. Insurance covered some of the damage. But there are some things money can’t buy.

Behind the rammed-earth walls of the Krause home was a lifetime’s worth of work documenting the type of environmental change they had just fallen victim to.

“I had 50 years of journals, field journals. Lost all of that. And I never had a backup of that. I would have all the names of the birds, I would have locations. And also my impressions, how I felt, how it made me feel there, because that was a very important part of my work. All of that data was there. It's all lost.” — Bernie Krause

Bernie's home sits destroyed after the 2017 wildfires. The rammed earth walls have black burn marks. Through a large opening in the walls rubble and ash are visible.

One of the most valuable possessions now turned to ash is the reel-to-reel recordings Bernie made of those habitats.

For 50 years, Bernie has pioneered the field of soundscape ecology, monitoring the health of ecosystems through the sounds they make. Sometimes the recordings were a beautiful symphony of a thriving ecosystem. Many times they were not. The most interesting material is often the quietest.

Part 2 - Back in Bernie’s studio

Bernie has a new studio. From the new home to the curtains covering the walls to muffle sound – everything had to be replaced after the fire. He has reflected on the fact that his recordings documenting the climate crisis were burned in a disaster spurred on by the climate crisis.

“The irony didn't escape me. But you know, I mean, life goes on. It’s ironic from the beginning.”

— Bernie Krause

Bernie, 82, started recording when audiotape was the only way to do it. It was only six months before the fire that he finished creating a digital backup of the recordings. Now, when Bernie connects to his computer, he can listen to a world of sounds he’s recorded.

Bernie was primarily drawn to natural soundscapes because of the therapeutic effect it had on him – especially its ability to control his ADHD. But listening, not looking, carries unique research benefits, he says.

“When our bodies are ill, it's always expressed through the sound of our voice. It's the same thing with a natural habitat. When a habitat is under stress, or it's undergoing some kind of change that's not healthy, it'll show in its voice.”

The voice Bernie speaks about isn’t an individual voice, like the call of one bird species. It’s the collective voice of the entire ecosystem. It includes the sounds of animals, which Bernie calls the “biophony” and also the sounds of the physical world, such as moving water and wind, and those of humans.

These changes can be laid out on a spectrogram – a visual representation of the sounds. The spectrogram shows the sound recording of the whole ecosystem in one single image. The higher the frequency of any sound, the higher it is on the spectrogram. The louder a sound, the more intense the colour is. Bernie has recorded healthy and unhealthy corals. When laid next to each other in a spectrogram, you can see and hear the life of a healthy one contrasted with a bleached ecosystem.

Some of the changes Bernie has recorded have been tied to the climate breakdown, though not all. He’s recorded whales, and how difficult it is for them to communicate by sound when loud ships pass by. Ultimately, his recordings show there are many ways humans have dramatically altered ecosystems.

These changes are evident in the Osa peninsula. In south-west Costa Rica, near the Panama border, the peninsula is renowned for its diverse wildlife.

Bernie has visited this area twice – once in 1989 and again in 1996.

Part 3 - Osa Peninsula

His first recordings revealed what you would expect in a tropical rainforest – sounds of rich biodiversity, and, the stars of the show, howler monkeys.

The howler monkey has its name for a reason. For a small animal, about 2 feet, it can make a surprising roar that can be heard over a mile away.

But its environment changed after Bernie’s first recording.

“I recorded at a particular spot, which I didn't know would be logged but when I went back in ’96 at that same location, that area had been logged illegally.”

“The logging companies had cut these 100 metres square grids through the forest. And so the howler monkeys that are specific to that area, and who always live in the canopy, almost never come down to the ground, weren't able to breach the gaps that were cut by the logging companies, weren't able to get food and in other areas of the forest that they typically had got to before. Consequently, there was almost no howler monkey voice or activity when we went back and recorded, even at the edges of the forest that hadn't been cut.”

The mantled howler monkey is now listed as vulnerable to the threat of extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The loss of tree habitat and tree fruit are a known pressure on their declining population. And it’s not just the animals who feel the negative effects of environmental changes.

Luisa Bejarano has been on the frontline of these changes her whole life. She’s a leader of the Ngäbe, an indigenous group in Costa Rica closely tied to the Osa peninsula, and the environment around it.

“We take care of the land because first of all, it nourishes us. And the forests and mountains are full of medicine. And the ancestors and elders have taught us that they're our siblings. What I've learned, what I maintain, I've learned from my ancestors, and in the same way, I pass it on to my grandchildren, my children.”

Luisa lives across from the peninsula in a rural home without electricity. She wakes up early and goes to bed when the sun goes down. In some ways her life has stayed the same during her 71 years. But the environment around her has changed since her childhood. She sees fewer of certain animals like deer. For Luisa, environmental damage means changes to how she can live her life.

“We need clean water, without contamination, so we can go to the river to bathe, and not get sick. So that's why we take care of the land and the water, the air. Because they give us life. We need them.”

Satellite data suggests that from 1979 to 1997, the Osa peninsula lost more than 30sq miles, or 8%, of the forest.

Threats to Costa Rica’s wildlife continue to evolve. In many ways, the country is leading the way in environmental protection. A 2012 petition spurred the creation of a law to ban hunting for sport. Despite this, poaching continues to threaten Costa Rica’s wildlife.

“People come in to hunt and they threaten indigenous people. They come at night. And no one can say anything because they're well-armed and threaten people. That's how they're destroying, wiping out the animals.”

Poachers target big cats, and one particular animal of interest – the jaguar. It’s a keystone predator, meaning the entire ecosystem relies on its presence.

Bernie says he would like to go back to Costa Rica and see what has changed – for better or worse.

But now that he’s in his 80s it’s not as easy to get around. He’s also developing macular degeneration in his eyesight and is losing his hearing.

“When you're deaf and blind, it really makes a difference. Especially when you're in soundscape ecology.”

He’s not worried about his legacy continuing: when he started, only a handful of people were working in the same field. Now he says there are thousands. He’s finding ways to carry on his work and is focusing on recording what he can closer to home.

Part 4 - Sugarloaf Ridge State Park

“Sugarloaf state park is an oak chaparral area. It's a very low-level mountain range that borders Napa and Sonoma valleys in northern California.”

Every spring on the same day Bernie records in the exact same location in the park. This has allowed him to mark seasonal and climatic shifts.

In 2011 a three-year drought began. The first year, the sounds of wildlife and the nearby stream were similar to recent years.

In his 2014 recordings, the stream was fading.

And in the 2015 recordings, Bernie found the sounds had changed dramatically.

“It was a silent spring.It was 15 seconds of just silence because that's what I recorded. There's no stream. There are lots of birds in the area, but none of them are singing.” — Bernie Krause

Sugarloaf Ridge state park was then hit by the same fires that took Bernie’s home. Bernie didn’t record immediately after because his recording equipment had been burned. The impact of the fires on the ecosystem can still be seen. His wife, Kat, gives a lot of thought to when and how the environment will bounce back.

“A very substantial impression that was left on me, on our community, and certainly on the areas that were burned on the wildlife and on the terrain, and on those habitats that are still going to take years to recover from.”

The fire recovery is something Bernie is keenly watching. In the autumn of 2020, another fire hit the park. This one burned more than 70% of the habitat during a serious drought. Listening to the recordings, the path to recovery is uncertain.

About a month before his next annual trip to the park, Bernie wasn’t sure what he would hear. No matter what, no ecosystem will ever sound the same twice.

“Sometimes a bird will sing out of one tree on your left or another tree on your right, sometimes they'll sing together, sometimes they will compete with one another. It’s always being tested to see how to survive and thrive. While I find context and content the same in a habitat, in other words, the same species, the same number of species, it will always be a different expression.”

Cultural / Context information for the jury

There are 300 million people with a visual impairment. [IOVS]

This includes a diverse spectrum of visual abilities — from colour affected vision to total blindness.

When focusing on the audio experience of Auditorial, we are focussed on users with such significant sight loss that they are typically reliant on assistive devices called screen readers, to navigate the web.

These technologies read webpages out, one chunk at a time, from top to bottom, left to right, in a robotic voice.

They are obstructed frequently by visual details, like ads, menu items, logos, hyperlinks, poorly labelled imagery, unnecessary decoration, videos, gifs. So the storytelling experience for someone using these technologies is extremely poor, laborious, inhuman, disrupted.

It can make something as simple as reading daily news a laborious challenge.

The internet as we know it, designed by sighted designers, is fundamentally biased toward sighted users.

Please outline the innovative elements of the work

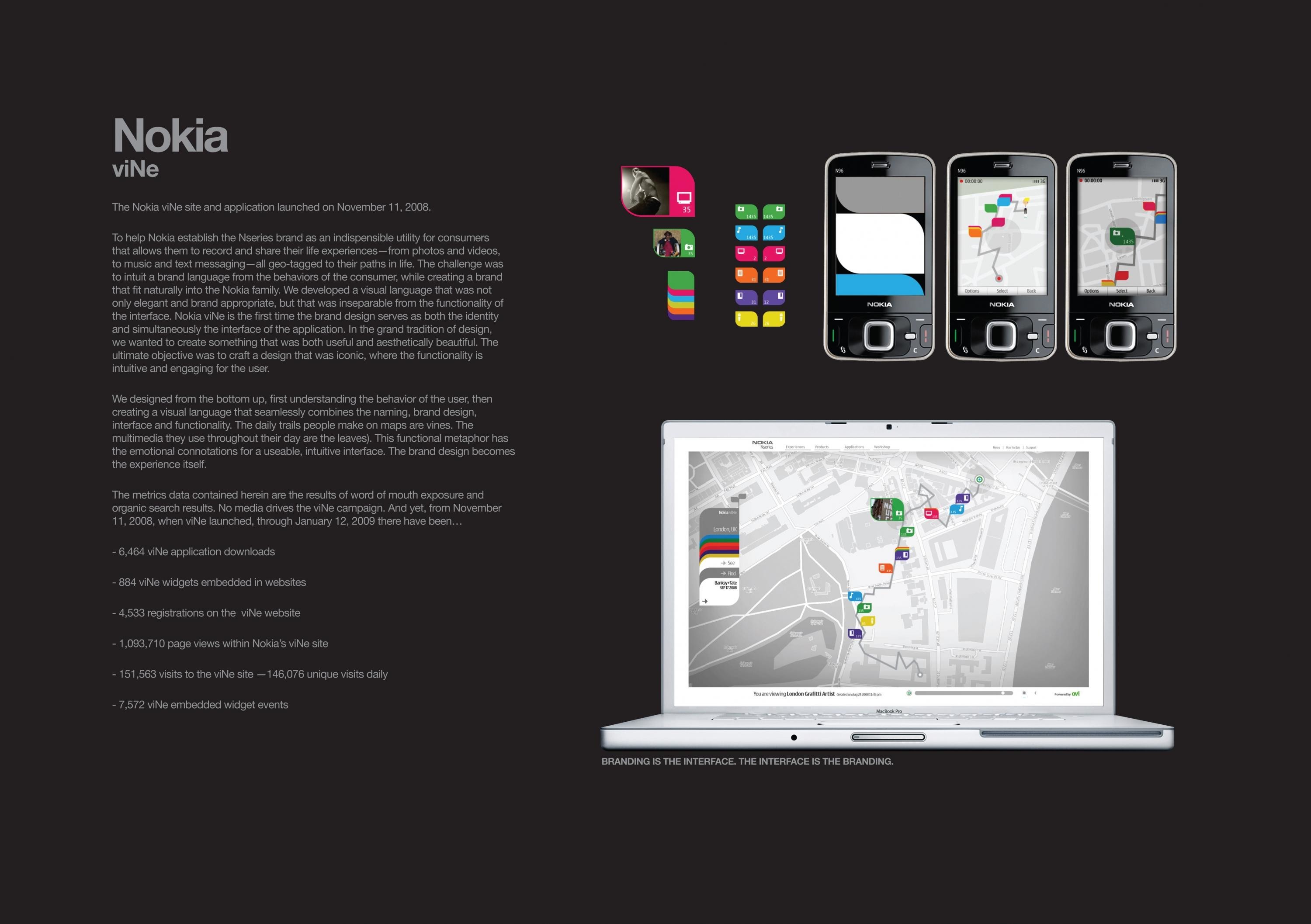

With Auditorial, you can customise the storytelling to suit your sensory needs —

If you are blind, you can simply hit play on a narrated version.

If you have sensitive hearing, you can remove ambient background noise.

If you are newly blind, and still learning to retrain your attention via your ears, you can slow the pace.

If you are accustomed to screen readers that recite information quickly, you can speed up.

You can turn on button noises, to confirm you’ve selected things successfully.

In addition to these adaptive controls, we implemented a new kind of screen reader introduction to help blind users understand what to expect from the website, developed a new narrative approach to alt-tagging to make imagery additive for blind readers, and used 'wholistic audio', which explains itself fully without any need to see any supporting visuals.

More Entries from Use of Audio Technology in Radio and Audio

24 items

More Entries from R/GA

24 items